The HR Leader’s Guide to Evaluating Leave Solutions

By AbsenceSoft

In this article, you’ll learn what long-term absence management entails, the challenges it creates, and the tools modern HR teams are using...

In this article, we explore why leave of absence management software is essential, the core features you should look for,...

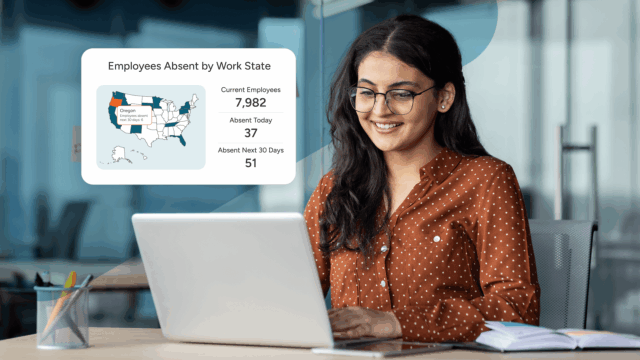

Real-time data and insights from leave technology can help you optimize your leave program and provide a better experience for...

Learn how modern leave and accommodations programs are critical tools for recruiting and retaining top talent.

In this article, we’ll answer a basic question: What is pet bereavement leave? We’ll also discuss why it matters and...

In this article, we define modern leave systems, explain their key features, and show you how they’ve improved leave management...

Requests for leaves of absence are rising, putting pressure on HR teams to respond quickly and compliantly. Learn key trends...

In this blog, we detail five reports your organization can use to streamline its workload and sharpen its approach to...

In this article, we show you AbsenceSoft harnesses automation to make your approach to FMLA faster and flawless.

In this article, we’ll show you how to build a leave and accommodation experience that offers employees genuine support and...

Explore key strategies for successful modern absence management in our detailed resource. Gain insights into optimizing processes, enhancing productivity, and...

Leave requests are rising sharply, and many HR teams are struggling to keep up, especially with over 200 federal and...

There are many tools used to help HR professionals do their job. How do all of these tools work together,...

By highlighting your organization's leave benefits, you can attract even the most selective candidates.

In this article, we’ll discuss the drawbacks of a manual approach and explain how you can leverage intelligent automation to...

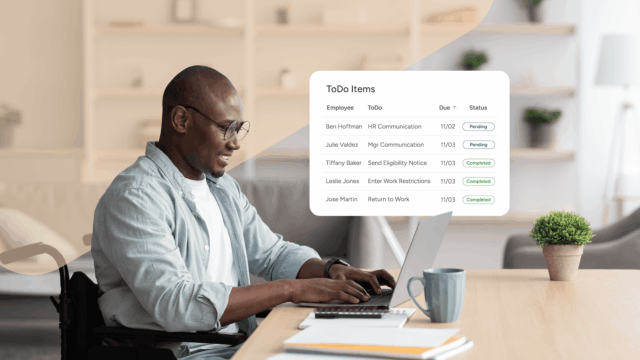

In this article, we discuss the tools of the trade that will equip your team to tame its workload, boost...

Learn what a clear, consistent, and compassionate intake process looks like, and why it matters for compliance, employee experience, and...

This article discusses why personalization is crucial to the success of your leave and accommodations program — and shows key...

In this article, we’ll explore key steps to FMLA compliance and delve into the strategies and tools HR needs to...

Ready to learn more?

Visit our resource center for curated articles, videos, webinars, and more, all researched and written by real, human leave and accommodations experts.